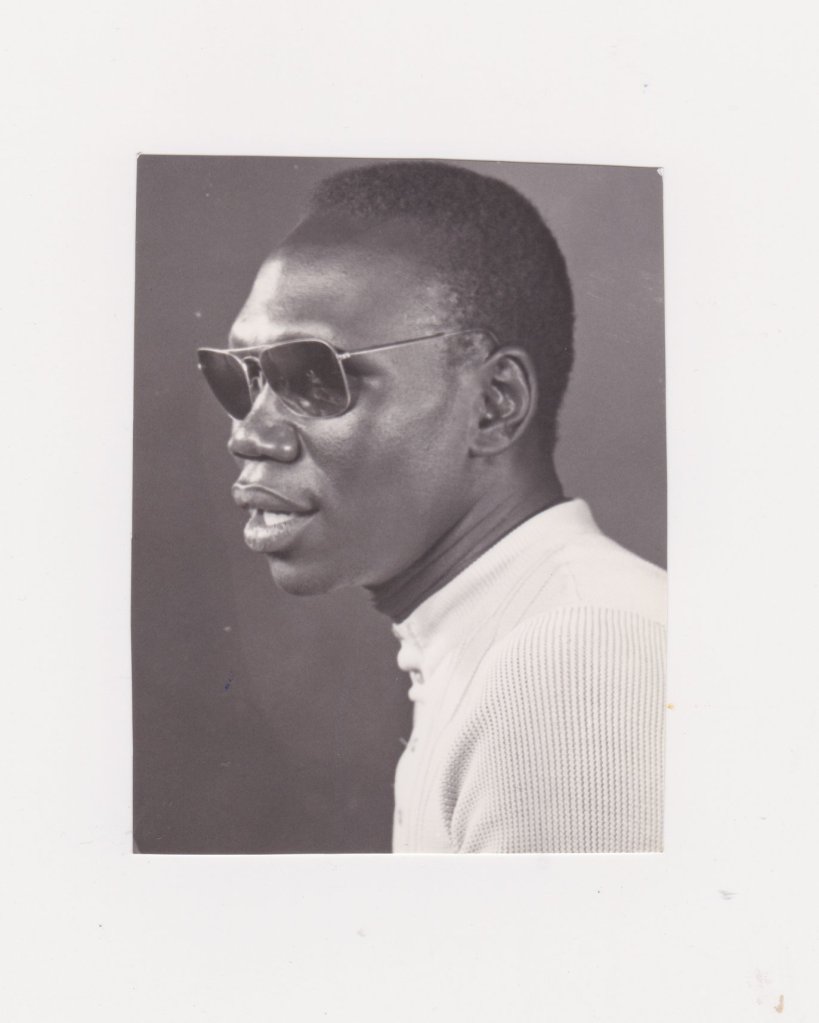

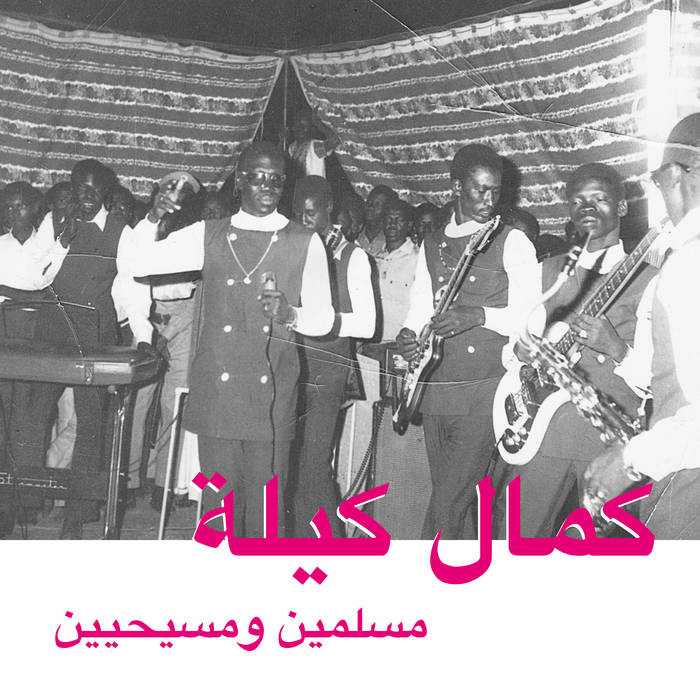

As an avid fan of music, I am no stranger to funk. I’ve sung every word to “Super Freak” back and forth to therapy appointments, I do my laps around my neighborhood to Songs In The Key of Life, I eat my solid bricks of tofu to There’s a Riot Going On, and I write to British Parliament while listening to The Parliament. I’m also no stranger to music from Africa; I’m familiar with quite a few classic records hailing from much of the continent’s west coast. Yet when I think of funk music, my mind doesn’t immediately turn to George Clinton. Similarly, when I think of music from Africa, I don’t instantly think of an artist like Fela Kuti. Instead, in either context, my mind tends to naturally laser focus on Kamal Keila and his album Muslims & Christians, recorded in 1992 and released in 2018 by German record label Habibi Funk.

Keila’s music captures something so primal within me that it might be infectious to others who breathe the same air I do. It’s rare I find music to be as genuine as Keila’s. He doesn’t just mean every word on this album; he belts his ideal at the top of his lungs for the world to hear, all the while delivering some of the most irresistible grooves to grace the earthlings that will never make it to my home star system in this lifetime. He’s never the most competent singer in the world, yet he delivers each line with the precise amount of passion they need to have. The deeply melodic motifs of this record end up being carried by his thick, warbly vibrato; you can tell on first listen nothing he says is a façade. His vocals are far too unpolished to be putting up any fronts. Keila is baring both his and the soul of his national identity to anyone who might dare to listen. Often he addresses the many political issues of his day that plagued the people of Sudan. Despite his flagrant calls for a unified Sudanese and African people all over the record, the country ended up splitting in 2015 after many decades of off-and-on civil war from several disparate groups. As a result, the album, much like Sudan itself, is separated into two sections: the largely Christianized and English-speaking south, as well as the Islamic and Arabic-speaking north. This historical context is vitally important to understanding Muslims & Christians and its raw emotional power. It is an album born from the chaos of a post-colonial, war-torn African country. Even in the bleakest of circumstances one could imagine in the modern world, the album stays consistently effervescent. It feels like it has to, like it has no other choice but to preach an optimistic message of unity with equally danceable funk jams, because the people needed that hope more than anything else.

The album kicks off with the song “Shmasha,” which quickly becomes a harrowing reminder of what the ravages of war and strife look like from the people who have to experience it firsthand. It serves as a lesson that conflict isn’t just redrawing the lines on the map, with Keila singing about losing his parents, as well as others who have lost their homes and children who can no longer go to school. Outside of its lyrical content, the song takes the opportunity as the intro track to ease the listener into its inner danceable nature, starting with dreamlike, reverb-soaked guitars as well as bluesy improvisation, which pairs with the somber tone of the song. After painting a vivid picture of the general wartime anxieties, Keila’s solution for which can be heard on the title track and “African Unity.” Despite the mixing issues, both tracks have great guitar solos that are just steeped in distortion. “Agricultural Revolution” is my favorite of the English side of the record. It features an extremely addicting and triumphant horn line that becomes the main appeal of this song. The plucked lead guitar also helps to add a percussive quality to the track, which quickly starts to become a pattern with many of the songs. It’s also around this time in the album that we start getting call-and-response background vocals that unfortunately suffer from being buried in the mix even more than the guitar solos do. Both Agricultural Revolution and African Unity are effortlessly funky, danceable, and intoxicatingly irresistible, like me after a bottle of Pink Moscato. After listening to the latter half of the record, you’ll be intensely familiar with the sound of the songs to follow. Bluesy solos, funk guitar licks, Keila’s forceful vocals, inspiring horn lines that make you feel like you’re overlooking a vast arid landscape, and intimately lo-fi production come to form such a rudimentary but absolutely unmistakable style.

After the song “Sudan in the heart of africa” comes the Arabic side. Despite my lack of ability to comprehend the language, I would have to say of the two sides it largely remains my favorite. Songs like “Taban Ahwak” and “Al Asafir” are so instantaneous with their appeal, both as songs you can bust a move to and also just as catchy tunes to just keep on repeat. Often I make up my own words to the songs in the Arabic tongue only to the detriment of passersby who stare at me yelling out nonsense sounds while I’m stuffing my shopping cart with solid blocks of tofu until it’s spilling out all over the grocery store floor. The latter probably has my favorite guitar riff in all of music, matched with a simple but effective drum pattern with staccato bass playing and a blaring horn section that just coalesce into an irresistible groove that the whole band is locked in on. Much of the same could be said of the former inclusion, but with the succinct and well-defined bass notes taking a much greater prominence in the mix.

Even the tracks that manage to take on a more solemn approach still end up having a rhythmic punch to them, akin to my boxing skills after I get reminded that billionaires exist. I wouldn’t say that they have that same catchy appeal that was so prevalent on previously discussed songs, but they still carry quite a bit of weight to them that makes them hard to ignore. “Ghali Ghali Ya Jinub” starts with a more weary horn lead that pairs well with both the slower tempo and the reggae-inspired rhythm guitar. “Ajamal Alyam” carries a similar-looking bundle on its back as it walks across the vast and seemingly endless ridges of the Sahara sand. That track opens with a sparse and gloomy guitar riff that ends up taking much more prominence than the horns do. As if its desert meandering finally resulted in finding an oasis to drop its bundle and settle down at, a little bit before the halfway mark the track ramps up into the album’s funkiest jam yet. Its lethargic demeanor explodes into a ball of groovy, bombastic energy. Keila’s spoken word rambling turns into the strong melodic presence we know him for on the back half. The tempo picks up, and it seems there’s real energy in everything the band does; all in lockstep with each other, they create as good of a send-off as the album could ever hope for. One last final hoorah, one last escapade through the tropical savannahs of the south and the hot deserts of the north. Up the White Nile to Juba, to where the two rivers split in Khartoum, we travel up that body that irrigates the land and gives life to both countries. Just like how we travel back in time to when Sudan was one, and everyone had access to both rivers without crossing intangible lines. In the end we realize that our journey with Keila painted as perfect a portrait as anyone could in the medium of music for those united lands, as The Kite Runner painted as perfect a picture as anyone could in the medium of literature for Afghanistan. The earth we look to as a homeland takes on a character of its own; no more did I realize this to be true than when listening to the soul of a land I will most likely never get to travel or experience for myself.

If you would like to support Habibi Funk and own a physical copy of Muslims and Christians you can do so here. You can also follow Habibi Funk on both Instagram and Facebook if you would like to stay caught up with future releases. Muslims and Christians can also be streamed on Spotify, Apple Music, and YouTube Music.

Leave a reply to Preserving an Ancient Local Tradition: Sounds of the Modern Day Griots – ARDENTLY Cancel reply