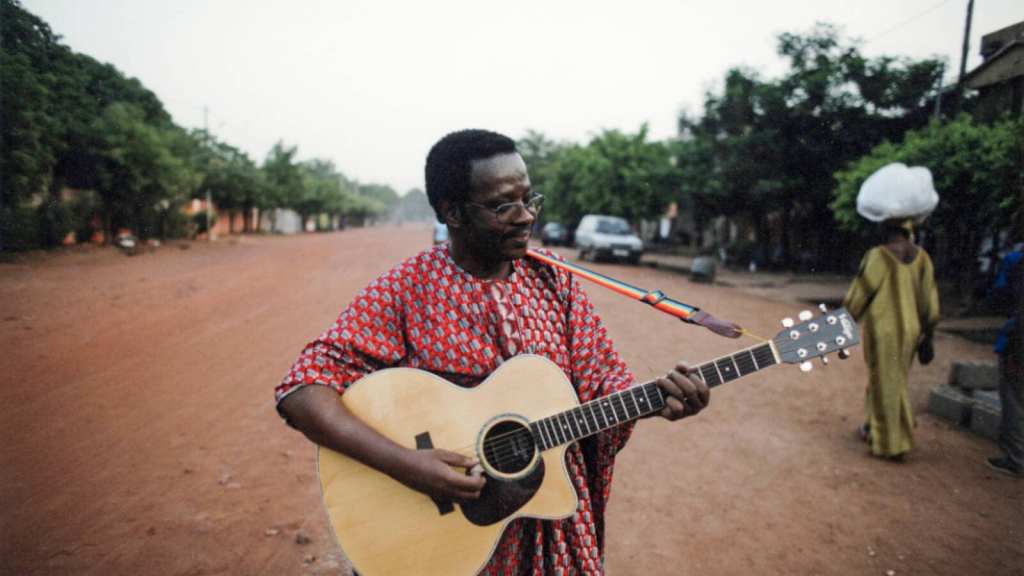

The last few albums I’ve covered on ARDENTLY have been kind of heavy. Genocide and losing loved ones are never easy topics to discuss, but they’re important and they’re not just something we can keep ignoring forever; at some point, they need to be talked about. Even if they’re cause of umbrage for others, if I didn’t at least address the context surrounding the records, I would feel like I’m shirking my journalistic integrity. That being being said, I think it’s time we break from this trend. I want to talk about something I love – a record I enjoy so much that I’ve annoyed many a coworker by playing it too loud over my bright cyan Bluetooth speaker. We’re heading back to Africa with this fantastic release from Mali: Ampsa: Le Tioko-Tioko by Idrissa Soumaoro Et L’Eclipse De L’I.J.A.

As I write this, the greater St. Louis metropolitan area is “cooling” down to a temperature that won’t immediately cause 3rd degree burns from just stepping outside for a nanosecond, but it’s still a little too hot for this extraterrestrial who is used to a nice, warm maximum of 56°F. These last few weeks have been brutal here in the 13th worst state in the union, so to reflect this extreme heat I feel like it would be fitting to review a record that paints the mental image in my mind of vast desert landscapes. I want something makes me feel like going across the Sahara all by myself, and like Mansa Musa, I think I’ve struck gold.

As I have alluded to in the past, I’ve listened to a lot of music from West Africa – a lot of which is from Mali. Amspa: Le Tioko-Tioko is just a brilliantly succinct distillation of much of the music throughout Mali – both Sub-Saharan and well within the confines of the desert itself. Some of the most apparent influence to me is the “desert blues” sound from the Tuareg people, which are a nomadic ethnic group that span across much of the Sahara, not just within Mali. I wouldn’t say that this record is dead ringer for the style as it feels so thoroughly influenced by any number of genres endemic to the nation state. However, the record does make sure to borrow a lot of the bluesy guitar embellishments and excessive use of hammer-ons that the Tuareg are known for. Bands like Mdou Moctar are an excellent modern band that works within the “desert blues” style that have managed to achieve some level of international notoriety.

It’s not just genres born of a specific ethnic group that are influential her – some of their synthesis comes from from styles that transcend across the whole the region of West Africa. The electronic organ all over this record does remind me of some afro-funk acts, like Marijata. Both the keys and guitar strumming can make for quite a few funky passages, but unlike Muslims and Christians, there’s no horns to dominate the whole track. It’s also worth noting that the percussive energy put on display all over the project in tandem with the call and response vocals does remind me quite a bit of the material that Fela Kuti and other afrobeat acts would release at the height of their creative output. More important than any sonic influence is how the record fits into the cultural landscape of West Africa and it’s many peoples, more specifically Ampsa: Le Tioko-Tioko belongs to a category we would now call “Mandé Music”.

Within the many Mandé ethnic groups there is a certain class of individual called the “griot“. A griot, within the rigid caste system of many Mandé-speaking peoples, served as storyteller or oral historian. Often, they would both perform and preserve the history of their people or fables through the medium of music. Traditionally, these sung, oral re-tellings would be accompanied by instruments autochthonous to these ethnic groups of West Africa. Chief among their native instruments is the Kora, a 21 stringed harp, but they would also play the balafon and ngoni, which were a wooden, xylophone-like mallet instrument and a small lute made from a gourd, respectively. Music made with these traditional instruments can still be heard today, but more often then not, the music made from Mandé peoples are often done with contemporary instruments, like in Ampsa: Le Tioko-Tioko.

This is to say, that ultimately it need not stick to any stringent sound for it still qualify as Mandé music. Rather, what qualifies it as such is the observation of long-practiced traditions within their ethno-linguistic group. Of course, music is a part of just about every culture to exist, but so rarely do we find a society whose mores mandate a class of musicians to perpetuate old folktales and histories for the rest of society. It’s this reverence of music and its ability to communicate that makes it Mandé. Whether or not the people making this music are born of griot blood is irrelevant, in this modern age they’re self-ordained griots.

Nevertheless, I still have to talk about the way the music sounds or else Shaelan won’t let me have any exposure to sunlight for the rest of the year; so review I shall. Really everything I have to say about the record would be nothing but gushing praise, which is fitting for the the name of the website, I suppose. The mixing on this album is phenomenal which is truly a rarity for many African albums released around the same time. Everything on this album is clear as a bell, which is great, because there’s so much amazing material on this thing that if any note were ruined by the awful mixing I don’t think my achy, breaky heart would understand.

The opening track “Fama Allah” opens with with explosive drum fill that’s just absolutely thunderous, paired with the electric organ really does have this absolutely electric quality to it. Not long after this thrilling opening, the track both drops tempo and volume, making way for this chanting group chorus. Eventually, the song picks back up with the acoustic guitar strumming and Idrissa Soumaoro singing and engaging in a call-and-response motif with the group singers. At this point in the song, the energy is at an absolute fever pitch. The almost-nine-minute song wastes no time – in the end it’s an absolutely fantastic winding journey in and of itself – a true dynamic rollercoaster of a music experience.

The rest of the tracks on the album are not nearly as extensive, yet they leave just as much of an impression. “Beni Inikanko” is the song with probably the most palpable influence from Tuareg music, despite them not belonging to the same broad ethnic, linguist or cultural families. The Tuareg and their music is a story for another day, my little river lotus blossoms. The song makes great use of this angular acoustic guitar line that both the lead and backup singer end up harmonizing with, all while doing more call-and-response vocals. The touch of reverb on the lead singer’s vocals brings the whole track together and helps foster a uniquely hypnotic, peaceful, and serene feeling that the song pulls off so effortlessly.

The second longest song of the album, “Nissodia”, is just as progressive and dynamic as the opening song. The track starts with the return of the much-beloved electric organ, supported with this super funky guitar lick. Along with the drum kit present in other tracks, there’s also a distinct sound of some hand drum akin to an instrument like the bongos. All of these elements together produce an oddly entrancing groove that quickly becomes irresistible. This backdrop put in place for the song makes for a great center stage for a galvanic organ solo, which becomes a real show stopper the more it progresses.

“Bimoko”, the closing song, sounds the most like it’s being fried from the sun’s generous gift of UV radiation out of the whole album. Again, we’re treated with these bluesy guitar lines, hand drums and a group chanting chorus. There’s another great organ solo around the half-way mark of the song, but it’s really not the driving force of the song. The blues-fueled acoustic guitar is really what set my ears ablaze. The organ solo makes way for an even better guitar solo that syncs up so well with the hand percussion. After the solo is done, it transitions extremely well back into chanting group chorus before fading out.

I usually like to write these conclusions with a sort of sentimental message about how music can connect to us in ways we typically don’t pay much mind. In this case, I think I’m coming up dry. For what may be my favorite album I’ve reviewed so far, and yet I have no greater meaning to impart on the reader? Perhaps that’s a not bad thing. Music can have a one-of-a-kind ability to connect with an individual that few other artistic mediums can ever dream of doing. That’s a special thing, to have something that you can relate to or take so much from that you feel like its an integral part of your being. However, sometimes you have something you enjoy so thoroughly, that has been a part of so many wonderful moments of your life, despite the fact that you have no connection to it. Sometimes you have forever music that is odd or strange to others, but to you it fits like a glove. This is my forever music. It isn’t for everyone, but it is exactly for me, and that’s what matters in the interim, before our cosmic time comes to a close and our successors find their own forever music.

If you would like to support Idrissa Soumaoro and his band, L’Eclipse De L’I.J.A. you may purchase the album on the label’s Bandcamp page. You may also stream it on Spotify, Apple Music and YouTube.

Leave a comment