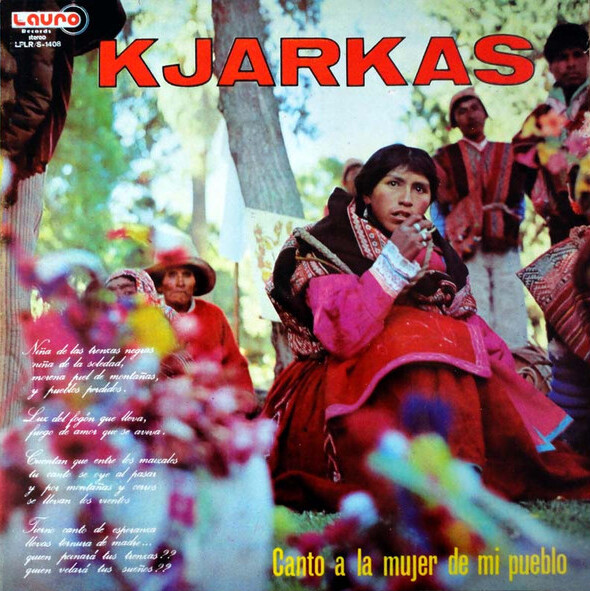

I’m always grateful for the opportunity that Shaelan has given me whenever I realize that I’ve spent too much time abducting lifeforms from other planets on the mothership, and remember I have 20 minutes to write another ARDENTLY review before the deadline. I’m still waiting on my internet service provider to send someone out to install a router on my ship, so I have to keep coming back to earth for the time being. She took a chance on a silly girl from Kepler-22b who really needs to fix her tractor beam after taking some beings off of Titan, and I will always be appreciative of that. Despite being the best, most responsible and humble music reviewer in the world, I have to be forthright about my faults when it comes to writing about albums. I’m unfortunately not super well versed on much of the music that comes from Latin America, which is becoming an increasingly large problem as I start to realize how much impact they have on our cultural zeitgeist here in the “first world.” I have a lot of experience with much of the music from Africa and really get into some obscure electronic dance music, metal and jazz records but I do have a few blind spots for someone in my position. This review is the start of my journey to hopefully becoming less woefully ignorant to musical achievements of the Latin American population, which I hope some of you fine folks reading along at home will join me on. It’s time to set myself and maybe others on the right path into being more worldly. After one more escapade of beaming up cows from factory farms, I’ll tell y’all about Canto a la mujer de mi pueblo by the Bolivian, Indigenous Andean band, Los Kjarkas.

Before I get into the review proper, it’s important we recognize that just because these people reside within Latin American and speak a language derived from Latin doesn’t necessarily mean they’re of Latin descent or Latino, which is a mistake I’ve made in several drafts of this review. The individuals who made this music are a native people of South America who settled in the Andes, where there is still a vibrant indigenous culture. This is born from that culture, and thus shouldn’t be seen as representative of any Latino population. This is partially why this record is eye opening for me, as I was unaware of any contemporary expression of Native South Americans, and thus believed much of the music from Latin America had a distinct Spanish and Portuguese influence, which ended up not being the case. Through reading this review I hope we can expand our idea of what Latin American music sounds like.

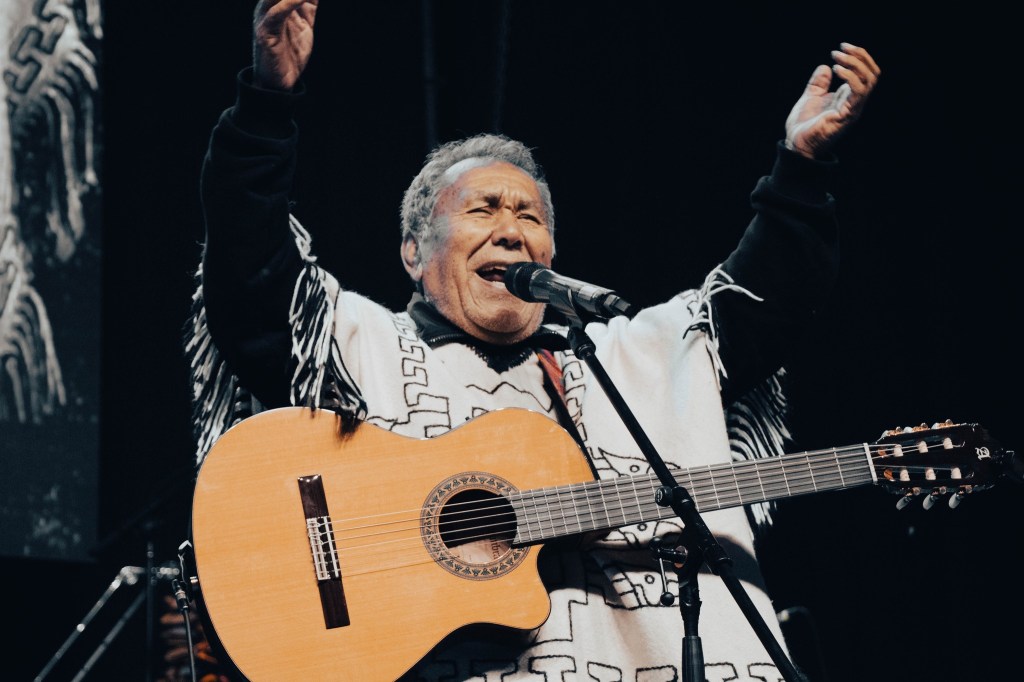

In more than a few ways this record reminds me of a previous review of mine, Renaissance de la harpe celtique. I would say both records inspire a certain level of emotional response from me, both of them give an enchanted idea of wanderlust as if I was exploring an ancient forest whilst listening. Sure, both records deal in tracks with mostly either contemporary acoustic instruments or folk instruments native to their ethnic groups, but this similar feeling that inspires me seems like it ought to run deeper then peoples making good use of instruments they have ancestral roots in. The first track “Wayaya,” begins with some absolutely fantastic acoustic finger-picked guitar that becomes supported by the strumming from the Andean charango, which tends to have a higher register like a ukulele. The song really picks up when the soft, muffled hits of the Bombo legüero start to make their appearance. It’s not long after that we start to get stunningly sung vocals, the lead of the band, Gonzalo Hermosa González, has an amazingly powerful and rich voice that really sounds like it shouts into oblivion, especially with the added touches of reverb that gives it a nice, understated echo. After González gives his verse, we start to hear a whole group chorus. Eventually, the Andean siku pan flute begins to harmonize with them, producing a really enchanting sound that pairs with the percussion, helping to inspire the sense of unparalleled exploration as if the music was purposely built to get me excited for a grand adventure that I’m supposed to embark on as I listen.

“Por un Mando Nuevo” delivers a similar vibrant forest aesthetic, again the finger-picked acoustic guitar becomes the backbone of the track, and functions much like harp does in Renaissance de la harpe celtique. Most of the songs are built along the plucked melodic lines where everything eventually grows out of, with all of the different instruments coming together to form a gorgeous piece that becomes a grand amalgamation of their cultural expression. Every building starts from just one brick and through mortar and time they become more than just a patchwork of building materials, instead they become something so much more, their importance only revealing itself when we begin to think of them as structures and not just individual bricks. One charango or powerful group chorus doesn’t make up a song on Canto a la mujer de mi pueblo, all the little pieces begin to snap together so effortlessly in your mind that you begin to realize just how much Los Kjarkas has this down to a science. Bit by bit, these songs progress and expand until you feel a magnitude of difference between the start and end of a track. Much like the comparison piece, this record feels like it’s at its strongest when you allow the song to grow out and change over time.

Even outside its more progressive elements, Los Kjarkas manages to create super captivating moments when we stumble upon uplifting musical motives, the title track is about as illustrative of this as anything can be. It starts with acoustic guitars, but unlike most of the other tracks, spends no time withholding the album’s more extravagant elements, almost immediately it allows the siku to majestically glide on top of the stringed instruments and jungle tree tops, as if it was bird of prey soaring through the air currents looking for its next meal. The siku and vocals exchange melodic lines with each other, which not only accentuates González’s vocal higher pitched, almost yelping, vocals, but also helps to bring out the chant-like qualities in their harmonized lines.

The songs that don’t have any lyrics especially remind me of Renaissance de la harpe celtique – just tracks that rely on a whole menagerie of melodies and motifs made from many native musical instruments. Songs like “Tata Sabaya,” “Phuru Runas,” and “Mamita Surumi” are some of my favorites – just by how much they divulge from the typical verse and chorus structure we’re used to in so much contemporary music. Despite not sticking so rigidly to this formula, these tracks manage to be so catchy. Songs like these also help to break up what little monotony there can be when listening to the whole record; I wouldn’t say that the songs necessarily flow together super well, but they’re all distinct and make for a listening session that comes by in what feels like a blink of an eye. Unfortunately, the Spotify release of the record has a few issues with the audio. Occasionally they sound like someone tried to scratch the record while it was being recorded. They’re most prominent on both the aforementioned “Tata Sabaya” and “Siempre He de Adortate,” but it’s a recurring issue across the record. It certainly isn’t a deal breaker but does partially dampen my excitement for an otherwise highly enjoyable album.

I’m not the only one throughout history that has been taken aback by Los Kjarkas compositions as the track “Llorando Se Fue” off this album has been the subject to many an uncredited interpolation. First of which was the international 1989 dance hit “Lambada”, but more recently the song “On The Floor” by Jennifer Lopez and Pitbull also made extensive use of the main melody from the original song. To me,, that’s a powerful testament to how big their appeal is as songwriters even outside of the niche audience that is intensely fascinated with music from every nook and cranny of the world, which is why I assume y’all are reading this, or it’s because I screamed at you to do it, that is also very possible. It isn’t even my favorite or the one I think resonates with me the most off the album, but it obviously left a huge mark on many others, something that few regional acts have the capability to do. Los Kjarkas have opened my mind to what music from both Latin America and Indigenous American peoples can sound like outside of my previously-held misconceptions, and they’ve opened up the dance floor for people who had little awareness of what the origins of the music they were listening to was. Los Kjarkas has room for all sorts of music listeners and I think that’s beautiful thing. They’re the little Indigenous Andean band that could.

If you would like to support Los Kjarkas, you can stream their album on Spotify, Apple Music and YouTube Music. As far as I can tell the band does not currently sell their music online neither physically nor digitally; the only way to obtain a physical copy is to buy it second hand.

Leave a comment